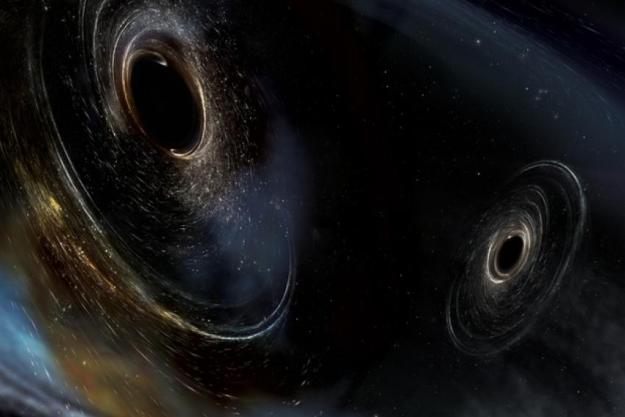

Even though black holes swallow anything that comes near them — even light — they are still possible to locate by looking for signs of their effects. Black holes are extremely dense, so they have a lot of mass and a strong gravitational effect that can be observed from light-years away. But the universe is a big place, and researchers are hoping that the public can help them to identify more black holes in the name of scientific exploration.

A project called Black Hole Hunter invites members of the public to search through data collected by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) to look for signs of a black hole. Using a technique called gravitational microlensing, citizen scientists will look at how the brightness of light from various stars changes over time, looking for indications that a black hole could have passed in front of a star and bent the light coming from it. This should enable the project to identify black holes that would otherwise be invisible.

One of the researchers on the project, Matt Middleton of the University of Southampton, explained in a statement: “Black holes are invisible. Their gravitational pull is so strong that not even light can escape, making them incredibly hard to see, even with specialist equipment. But that gravitational pull is also how we can detect them because it’s so strong that it can bend and focus light, acting like a lens that magnifies light from stars. We can detect this magnification and that’s how we know a black hole exists.

“We know our galaxy is teeming with black holes, but we’ve only found a handful. You could help us change that.”

Interested members of the public can get to work looking for black holes at the Zooniverse website, which also hosts other citizen science projects and includes training on how to spot indications of a black hole.

“Anyone of any age can do this, and you don’t need to be an expert to take part,” said another of the researchers, Adam McMaster. “All you really need is an interest in space and as little or as much time as you can give for looking at the graphs and helping us spot the patterns that could reveal a black hole. Your work will directly contribute to real scientific research, and you’ll be helping to make the invisible become visible.”

Editors' Recommendations

- NASA 360-degree video shows what it’s like to plunge into a black hole

- Stunning image shows the magnetic fields of our galaxy’s supermassive black hole

- Record-breaking supermassive black hole is oldest even seen in X-rays

- Measure twice, laser once. Meet the scientists prodding NASA’s first asteroid sample

- Swift Observatory spots a black hole snacking on a nearby star